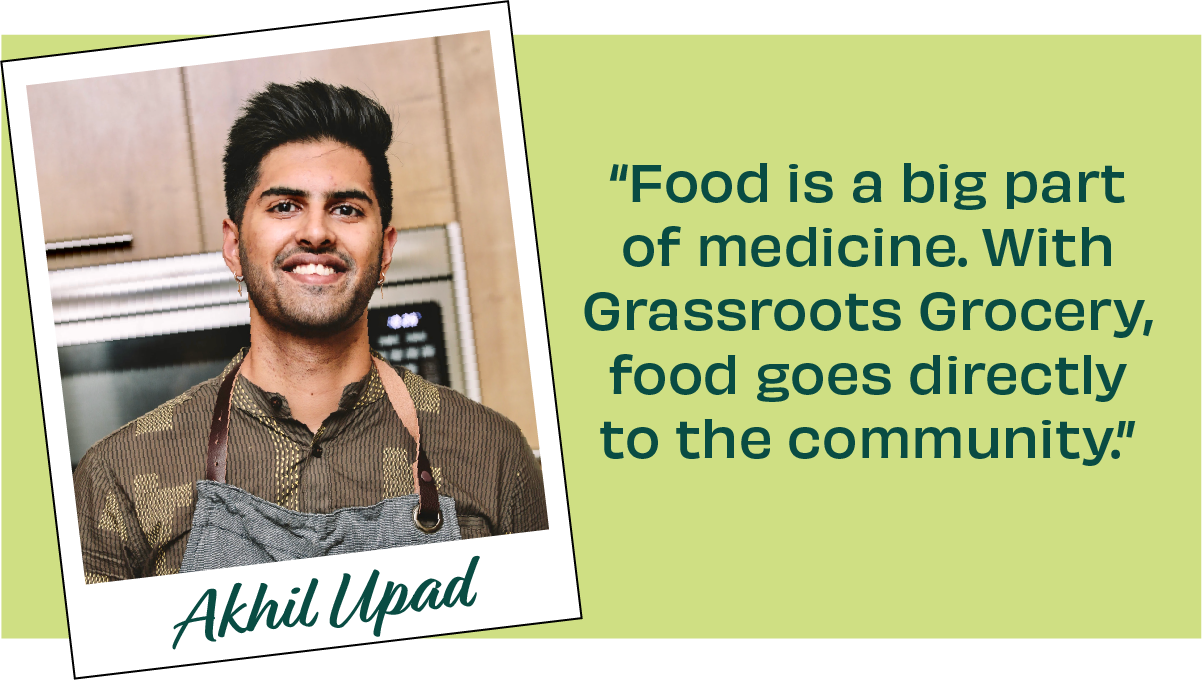

Meet Akhil

Each month Akhil Upad can be found at the Grassroots Grocery Produce Party, helping get quality produce to the food deserts he worries about.

Fresh healthy produce, he says, is not only basic to health.

“it should be part of medicine.”

Akhil Upad, a researcher and medical student at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, has a vision. His future medical practice will include a kitchen for patients.

And not just any kitchen, but a teaching kitchen, where patients can learn to cook healthy meals using ingredients they already have at home.

His is a deeply felt need that is partly based on research that has given him what he calls the “micro” view: how much the human body and life itself hinges on healthy food on a cellular level. “Food is a big part of medicine,” as he puts it.

We listen to Akhil’s life during COVID in Atlanta where his mother helped pull together “a community of Indian aunties” as he would fondly describe them, all around metro Atlanta. “They would just cook Indian food, which is mostly veg. So I would run a team of drivers, while partner organizations distributed that to those in need in Atlanta.”

And then there is the Sewing Tin.

The creation of Akhil and his partner and chef, Aditya Mishra, the Sewing Tin is a supper club, offering, let’s not be shy…oh so tempting food, often featuring rescued produce from Grassroots Grocery in his meals. The club’s name itself is a story you will learn here, nostalgic to many South Asians who have come to the U.S. and, as we might have guessed, is inflected with a note of childhood insecurity about food. But more on that later.

Through it all, one feels Akhil’s profound belief that food is basic to any society: to our physical health, mental health, to unity and love.

Childhood nostalgia

Q . You are very accomplished, a researcher, and active in the movement against food security. With all due respect, do you mind if we start with The Sewing Tin?

Akhil: Sure why not?

Q. Because you've described how much food affects a culture.

Akhil: The Sewing Tin is the name of our monthly supper club. Grassroots Grocery often supplies rescued fresh produce and we are happy to place a card at each place setting about the neighbors helping neighbors movement. The name, Sewing Tin, is a tribute to the iconic box of butter cookies that has dominated immigrant households and has led to an almost universal experience among the children of immigrants: we were hungry kids craving for dessert only to find sewing supplies. Our parents would use the tin as storage for threads, needles, scissors, and anything sewing-related. We remember that, and it is also nostalgic.

Q. Children’s experience with hunger is a lasting memory.

Later in life you became engaged with food in a scientific way.

The “micro view:” food and health

Akhil: I'm from Atlanta, Georgia. I went to Georgia Tech studying biochemistry, and I really wanted to do bench-to-bedside research. I wanted then to become an MD, PhD.

After I graduated, I came to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center here in New York. I worked in a research lab under Doctor Yael David. She put me on a project that I really enjoyed, exploring a link between nutrition, metabolism and the onset of chronic disease like diabetes and cancer. But things shifted fast.

Q. Along came COVID.

Akhil: Right. The lab shut down, everything closed. There didn’t seem anywhere to go except back to Atlanta. But that’s when things changed for me.

Q. Your mother’s project against food insecurity.

Akhil: My mom was involved in a very cool food insecurity relief effort that was very much started at a grassroots level. My parents are from India, immigrated here; I was born here. There was a community of Indian immigrants in the north Atlanta suburbs. They worked through an organization called the Dr. Parnerkar Life Management Foundation.

A group of my “Indian aunties” would cook Indian food, which is mostly veg. You can make a lot of it pretty easily and it's relatively cheap. We'd make these potato dishes, these chickpea dishes, okra dishes.

I would pack and deliver this food.

Empowering patients to eat well

Q. Coming back to New York, you found another turn in the road?

Akhil: Well yes. I had taken a shift where I’m like hey, you can create the best treatment. But what is the use of that if you don't have the money or resources to get produce and the space to cook it? So I shifted to medicine, to empower those patients through whatever resources they have to eat well and you know, treat their bodies well, given whatever they're going through. That stirred my interest in food insecurity.

Q. You came across Grassroots Grocery at about this time?

Akhil: It was a structural partnership at first. But I think Dan is a really compelling face for the organization.. He really pulls it together and involves the community.

And I think one thing he stressed a lot is how hyperlocal it is. Food goes directly to the community. And so I think as a result, you just get a sense of belonging when you're there and you're doing something affecting the people around you. It seems that Grassroots has a solid community to be backed on. (I appreciate) the volunteer base. The produce parties just make it different. It's lively!

Sugar stress and inequality

Q. Did your experience at this time, including with Grassroots, share an outlook with the Social Determinants of Health movement?

Akhil: Yes. I’d already seen while I researched at Sloan-Kettering how sugar stress can lead to the progression of cancers and diabetes and other disease states. Now, in New York there are broader social problems with income, housing, etc. which are like a self spiral.

So I felt that healthy food and healthy produce is a link to it, another determinant. Why do so many people not know where their next meal is coming from? There are many reasons. You can’t address just one cause.

Q. I’d love to hear more. I hope we will talk further. See you at the Produce Party!

Akhil: Yes for sure.